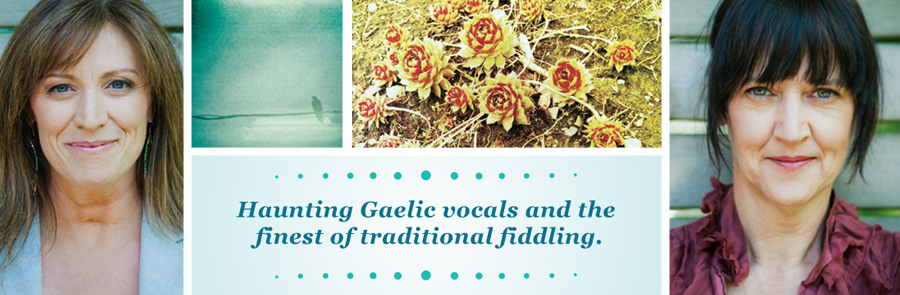

Cape Breton soul inspires Mary Jane Lamond and Wendy MacIsaac

The soul of a land and its inhabitants is a hard thing to put into sound, but Nova Scotia singer Mary Jane Lamond and fiddler Wendy MacIsaac have achieved that with their album Seinn. The hills, glens, coves, and villages of Cape Breton—and the people who live and work there—inspire the musical portrait of the island, which was settled by Gaels from Scotland some 200 years ago.

Seinn presents a series of closely linked musical contrasts. Lamond’s haunting songs in Gaelic alternate with instrumental sets of tunes that cleverly shift their tone between darkness and light, driven by MacIsaac’s fiddle. Songs of joy follow laments, and the stylistic approach is by turns starkly traditional and brightly contemporary.

“It’s something I’ve tried to do with all of my own recordings,” says Lamond, reached in Montreal. “Wendy’s have been fairly straightforward, and she said she wanted to do something with quite intricate arrangements and soundscapes. I think Seinn is a real balance of our sensibilities. Wendy had a lot of ideas.”

The album was two years in the making. Lamond and MacIsaac got help from 20 guests, as well as core band members guitarist and banjo-player Seph Peters and multi-instrumentalist Cathy Porter. The textures are richly varied. One of many highlights is the long set “Angus Blaise”, named after one of MacIsaac’s two young sons, which includes three of her own tunes. Her maverick cousin Ashley MacIsaac is a special treat, playing piano with gusto and imagination.

Lamond has devoted herself to keeping the light of Cape Breton’s song heritage alive and fresh, reinvigorating North America’s only Gaelic-speaking community with the music that, perhaps more than anything else, has helped keep it together. The island’s songwriting tradition in Gaelic continues. The longest track on Seinn, “Tàladh Na Beinne Guirme/The Blue Mountain’s Lullaby” has lyrics by local poet Jeff MacDonald.

“Jeff lives just down the road from me,” says Lamond. “It’s a fairly sentimental piece, talking about the coming of the Gaels to that particular area. I can see the Blue Mountain out of my living-room window, and in the song he talks about how the mountain hears people coming and responds to their songs. Then they begin to leave—and he says he’s there alone, but he’s going to continue to sing.

“We’re getting down to very few native Gaelic speakers now, but there’s a group of young people who through mentorship programs have become very good, idiomatic and natural. They get together to sing because they love to, not because they want to be performing artists. There’s a vibrant scene. I was one of the mentors and had people staying at my place. I called it the Gaelic flophouse.”

Lamond’s dedication to the language has won many fans in Scotland and Ireland, and she and MacIsaac recently returned from major international festivals in Glasgow and Dublin. Several smaller tours are planned for this year in North America. “With Seinn I’ve been really enjoying performing again,” says Lamond. “I toured like a maniac for seven years in the late ’90s and early 2000s—and I wore myself out. I don’t want to do that anymore. It’s been a long time since I felt I had something like this that I really want to get out and do.”